II. The United States Mortgage Market: A Complicated Balance Between the Private and Public Sectors Leaves Borrowers Overextended

Before the Great Depression triggered a widespread housing market collapse, the federal government was not directly involved in the mortgage market. Instead, prospective borrowers in search of financing could turn only to a few private institutions for help. From the early 1860s to 1913, most commercial banks were barred from issuing loans secured by real estate, rendering them an ineffective source of mortgages for consumers.7 In their place, Building and Loan Associations (B&Ls), an early 19th century import from Great Britain, became the dominant institutional mortgage issuers as they spread throughout the rapidly urbanizing country.8 These institutions, which tended to be small and localized cooperatives, used so-called Share Accumulation Contracts as their financing structure. These allowed borrowers to repay mortgage debt over time by buying shares of the association, which differed from the balloon payment model that most commercial banks used at the time. By the 1920s, B&Ls operated nearly 13,000 locations, served more than 11 million members, and financed half of all new housing built that decade.9

The Great Depression precipitated a simultaneous banking system and housing market collapse that exposed the underlying fragilities in the U.S. mortgage market which, until then, had exclusively relied on private capital and lenders. In the 1930s, one-third of the roughly 12,800 B&Ls that were operating in 1929 failed.10 So too did an additional 9,000 commercial banks, wiping out nearly nine million household savings accounts.11 At the same time, cratering home prices and steep unemployment acted as a “double trigger” for widespread foreclosures, while new housing construction ground to a halt as investment dried up.12 In response, President Franklin Roosevelt — for the first time — wielded financing power of the federal government to stabilize the home mortgage market and stimulate flows of lending and borrowing.13 In doing so, he created the mortgage system we still have today — one of complicated coexistence between private financial institutions and the federal government.14

in 1933, Congress created the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) to directly refinance the mortgages of struggling borrowers.15 By the time it halted its lending activities in 1936, the HOLC held approximately 1 million loans — roughly 10% of all nonfarm owner-occupied homes — and had helped more than 800,000 families avoid foreclosure.16 To revive shell-shocked lenders and jumpstart new construction the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) was created in 1934.17 A permanent agency, the FHA insured privately-issued mortgages and required lenders to offer loans at lower interest rates with longer durations than most private institutions were willing to offer at the time.18

Despite these measures, the U.S. housing market had not fully recovered by the late 1930s, and the federal government responded by chartering the first GSE. The Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae), established in 1938, issued bonds for purchasing mortgages at par — without interest rate risk — to give investors the confidence to invest in communities with little local capital.19 This provided liquidity to the market by making additional sources of financing available for new loans.20 But the economic forces of the Great Depression, followed immediately by World War II, caused the mortgage market to remain stagnant in the years following the creation of Fannie Mae.21

In 1944, anticipating the imminent return of millions of service members at the end of World War II, Congress passed the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act (or, G.I. Bill of Rights), which created the Veterans’ Home Loan Program.22 Although the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) did not finance the loans directly, the new program did cap interest rates charged to borrowers, eased down payment requirements, and provided a partial guarantee against default that encouraged banks to lend to returning veterans.23 These generous terms made the loans popular: Between 1949 and 1953, they accounted for roughly 24% of the market.24 By 1955, the VA had granted more than four million home loans, totaling $33 billion in value.25

These new federal housing finance institutions and mortgage programs, along with rising real incomes, favorable tax treatment of owner-occupied housing, and liberalizing terms for FHA loans, enabled an historic post-World War II housing ownership boom.26 In 1940, about 44% of Americans owned their home; By 1960, 62% did.27 Research suggests that federal intervention — in particular the availability of long-term, fixed rate, low-down-payment mortgages like those available from the VA and FHA — accounted for approximately 40% of the overall increase in homeownership during this period.28

During this time, homeownership opportunities expanded across both urban and rural areas, and enabled younger Americans to buy homes at dramatically higher rates than earlier generations.29 While wartime economic priorities had slowed private housing construction, the postwar surge in demand sparked an unparalleled building boom: New single-family starts rose to 1.7 million in 1950 — an increase of roughly 2,000%.30

By the early 1970s, Savings and Loan Associations (S&Ls, or thrifts) — the institutional successors to B&Ls after post-war federal changes to chartering — were vulnerable to rising interest rate risk. Congress then established a second GSE, the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (Freddie Mac), to purchase long-term mortgages from struggling thrifts.31 This increased their capacity to fund additional mortgages and keep pace with rising demand for homeownership.32 Around this time, Congress also authorized Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to buy and sell conventional mortgages.33

By the early 2000s, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac had both been converted to private, shareholder-owned corporations.34 But their status as GSEs created a dangerous misconception that the federal government would unquestionably bail them out if they ran into financial trouble. As for-profit corporations, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac began adding higher-yield (and higher-risk) private-label securities to their investment portfolios, which were increasingly backed by sub-prime mortgages.35 When the sub-prime mortgage bubble burst in 2007 and helped trigger the Great Recession, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac suffered huge financial losses and were placed into government conservatorship — where they remain today.36 By the end of the crisis, millions of families had lost their homes to foreclosure, over seven million workers had lost their jobs, and over $19 trillion in household wealth had been wiped away.37

Today’s mortgage finance system reflects this historical tussle between private players and the federal government — culminating in a complicated network of public and private institutions and financial activities that can be difficult for borrowers to navigate.

Of the 51.4 million outstanding residential mortgages in the U.S., more than 41.3 million (over 80%) are either government-sponsored or have been acquired by the GSEs.38 Just over 10 million (less than 20%) are conventional. Though the federal government is critical to backstopping and keeping capital flowing through the mortgage market, it issues very few loans directly to consumers. The VA’s Native American Direct Loan (NADL) program for Native veterans and the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Section 502 Direct Loan Program (42 U.S.C. 1472) for low-income rural households are the only federal programs that grant consumers direct access to residential mortgage financing from the government.39 Though vital to eligible beneficiaries, these programs are strictly limited in scope. Since 2010, only 111,888 Section 502 Direct Loans have been issued to low-income and very-low income borrowers — fewer than 8,000 per year.40 And from fiscal years 2012 to 2021, NADL originated just 89 loans to veterans in the contiguous U.S., 91 loans in Hawaii, and none in Alaska, accounting for less than 1% of an estimated eligible population of 64,000 to 70,000 veterans.41

As the U.S. mortgage market grew larger and more complicated throughout the 20th century, it created opportunities for intermediaries. One type of intermediary — the mortgage broker — exemplifies how middlemen were able to forge a foothold in the mortgage market as it became increasingly financialized. The mortgage broker industry which took shape with the advent of the secondary market and mortgage-backed securities, emerged to help consumers navigate the newfound complexities of mortgage financing and institutions.

Since the 1970s when mortgage brokers first became popular in the U.S., the industry has come to serve a large role in the homebuying process. Today, mortgage brokers find and recommend loan terms to borrowers for a fee. In 2022, nearly a quarter of new home purchases involved a mortgage broker.42 But a borrower can feel coerced into using a mortgage broker if they are not confident about navigating the homebuying market on their own. And brokers, who maintain relationships with banks and are typically compensated a 1% to 2% of the loan value, can be incentivized to steer borrowers to certain lenders, even if those institutions aren’t offering the most competitive terms.43

A series of recent mortgage brokerage lawsuits, as well as growing concern from consumers, has triggered increased government scrutiny. In 2024, the Consumer Financial Protection Board (CFPB) announced it would examine mortgage broker compensation rules and practices to curb the all-too-common schemes that steer clients to certain lenders.44 For instance, the CFPB filed a lawsuit in 2024 against mortgage lender Rocket Homes, which had been giving kickbacks to real estate brokers and agents in exchange for directing homebuyers to its sister company, Rocket Mortgage.45 In April 2025, the Ohio Attorney General’s office filed suit against the United Wholesale Mortgage (UWM) for colluding with brokers to funnel loans back to itself while charging borrowers above-market rates and improper fees.46 According to the filing, 99% of the $605 million in mortgages it issued from 2021 to 2023 was directed back to UWM.47 Though many homebuyers use brokers without complaint, their prevalence as an intermediary in a complex financial marketplace with operations obscure to most consumers presents opportunities for such scams.

Though intermediaries like brokers emerged to help consumers, wading through the mortgage market’s many layers of banks, financial intermediaries, and eligibility terms and paperwork creates undue mental strain for prospective buyers. A survey on homebuyer stress found that the vast majority of people who don’t yet own a home are anxious about the process.48 Seventy-four percent found the homebuying process complicated, with 74% citing financing the main driver of their anxiety — more than that which cited getting the down payment together. Nearly two-thirds of men and women find buying a home more stressful than getting married.

The history of the U.S. mortgage market illustrates a persistent tension between private financial institutions and federal intervention, resulting in a system that is both essential and deeply complicated for borrowers. From the early reliance on localized B&Ls to the creation of GSEs like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, federal involvement has consistently sought to stabilize the market and expand access to homeownership. Yet, the coexistence of private profit motives and public backstops has created a complex web of mortgage lending institutions, intermediaries, and opaque costs — resulting in consumers spending unnecessary time, money, and energy trying to access home financing. Even as the federal government has mitigated risk and injected liquidity at critical junctures, the U.S. mortgage market remains layered, confusing, and prone to systemic vulnerabilities.

III. From Backstop to Frontline: An Agenda for Reviving Federal Power to Reduce Mortgage Costs for Families

Though the federal government has propped up the mortgage market for generations, it is far from using its full power as a direct market participant to lower costs and reduce burdens for families. Instead of the status quo where the government’s role is submerged within a network of public-facing private financial firms, we outline the following assertive interventions the federal government could enact to bring down housing costs. While the following policies will not completely solve the housing affordability crisis that affects more than 44 million renters in the U.S., they could make housing more affordable for the millions of families struggling to buy or stay in their homes.49

Lowering the Cost of Mortgage Insurance

Each year, millions of homebuyers must take out costly mortgage insurance to protect their lender from the risk of their default. Government-backed mortgages require the borrower to purchase mortgage insurance50 in the form of an Upfront Mortgage Insurance Premium (UFMIP) and an annual Mortgage Insurance Premium (MIP) paid monthly.51 Conventional mortgages require private mortgage insurance (PMI) for the approximately 800,000 homeowners each year who put down less than 20%.52 Approximately 34% of all loans originated between 1999 and 2022 required mortgage insurance.53

Most borrowers do not realize that mortgage insurance protects the lender, not the borrower, to induce lenders to do more lending.54 In theory, it also benefits homebuyers because, without it, lenders would require larger upfront down payments. Although mortgage insurance covers the risks associated with a low down payment, borrowers often pay for it over the life of the loan. While not the most expensive line item when buying a home, mortgage insurance can tack on thousands of dollars to an already-expensive process. PMI runs families an average of $2,110 per year, or $176 per month.55 In some states, PMI costs as much as $6,210 per year, or over $500 per month. For FHA insurance, premiums cost an average of $1,650 per year, or about $137 per month.56

The federal government already has several options for relieving mortgage insurance costs for borrowers. First, without Congressional action, it could lower the rate at which the MIP is charged to borrowers. In fact, it did so as recently as 2023, when the FHA announced a 30 basis-point reduction to annual premiums.57 Although the reduction applied only to forward mortgages, it saved more than 1.1 million borrowers each an average of $453 annually.58 Total savings for these borrowers over a loan life of roughly 10 years is forecasted to amount to more than $5.1 billion.59

Though the capital ratio of the Mortgage Insurance Fund, which acts as the insurer of FHA-backed mortgages, must be at least 2% under the National Housing Act of 1938 (12 U.S.C. § 1711(f)(2)), it is currently nearly six times that at roughly 11.5%.60 Over the last 10 years, the fund’s capital ratio has increased — even after FHA lowered premiums in 2023 — suggesting that there is room for significant additional MIP rate cuts.61 Because FHA loans account for roughly 15% of all mortgage loans, lowering the MIP rate would deliver savings to millions of families, especially for the first-time homebuyers holding more than 80% of FHA loans.62

Second, the federal government could shorten the lifetime of MIP payments for government-backed loans by requiring automatic termination earlier or at a lower loan-to-value (LTV) ratio than currently required. If a borrower puts down less than 10% on government-backed loans, the MIP will be assessed for the lifetime of the loan or until the borrower can refinance.63 If a borrower puts down more than 10%, MIP payments are automatically cancelled after 11 years. PMI, on the other hand, is supposed to be cancelled automatically at 78% LTV, and borrowers can request early cancellation at 80%.64 However, many borrowers report that servicers fail to terminate their payments when they hit the threshold.65 Policymakers can amend Section 4902 of the Homeowners Protection Act (12 U.S. Code § 4902) to enable earlier cancellation of PMI, which is enforced by the CFPB.66 For FHA insurance, the FHA can amend its rule (24 C.F.R. § 203.318 & § 203.512) to allow earlier termination of MIP payments.67

Expanding Access to Assumable and Portable Mobile Mortgages

Whether families need to buy a new home as they have more children or adjust to life events such as a job in a new city, elevated interest rates and high mortgage costs can trap families in homes that may no longer fit their circumstances — and force them to trade-in low-rate mortgages for more costly financing. The U.S.’s elevated interest rates are making new mortgages much more expensive and “locking in” homeowners who bought when rates were lower. Today, empty nesters, for example, own twice as many large homes as Millennials with young children, worsening housing shortages and making it harder for families to find homes that meet their current needs.68

To address this, policymakers can expand access to an underutilized home loan product that could deliver thousands in cost savings to homeowners each year: mobile mortgages.

Prior to the 1980s, federal law allowed homebuyers to take on the terms of a seller’s existing conventional mortgage.69 Called “assumable” mortgages, these arrangements required a lender to forego executing a due-on-sale clause within a mortgage contract.70 Due-on-sale clauses enable a lender to declare a mortgage loan immediately due and payable if the real property securing the loan is transferred without the lender’s consent, thereby functionally rendering an assumable mortgage impossible and forcing homebuyers to take out new, market-rate loans.

Assumable mortgages were not particularly popular until the 1970s, when a prolonged period of elevated interest rates meant homebuyers faced dramatically higher mortgage rates on new loans than most home sellers’ existing mortgages.71 During this time, the Federal Reserve raised interest rates as high as 19% and the 30-year fixed rate mortgage peaked at 18.4% in October 1981, hovering at or above 10% through the early 1990s.72 Mortgages that had been taken out in the years prior became incredibly attractive to buyers otherwise facing double-digit market-rates.

As more homebuyers sought to take advantage of assumable financing, a series of high-profile court cases triggered regulatory changes intended to limit their use.73 In Wellenkamp v. Bank of America, 1978, the Supreme Court of California restricted the automatic enforcement of due-on-sale clauses and protected buyers’ ability to utilize assumable financing.74 This ruling, and a series of state laws that also safeguarded assumability, were a victory for consumers. But banks and other lenders — which wanted borrowers to take out more profitable higher-rate loans — strongly opposed mobile financing and lobbied for legislative changes to codify their ability to execute due-on-sale clauses.75 The political contestation of assumable financing set the stage for the Garn-St Germain Depository Institutions Act of 1982 (Public Law 97-320), which, among other deregulatory matters, granted lenders the right under federal law to enforce due on sale clauses, pre-empting state laws and court rulings prohibiting them.76 Garn-St. Germain freed lenders from virtually all restrictions on the use of due-on-sale clauses, largely ending the option for borrowers to take advantage of assumable financing.77

Via a similar mechanism, families could take — or “port” — their mortgage with them when they move to a new home. So-called “portable” mortgages would allow homeowners to transfer the terms of their current mortgage to a new property, using the sale of one home to pay off the balance of their existing mortgage. Because, under this scenario, the homeowner has already been assessed for creditworthiness, a portable mortgage wouldn’t necessitate an entirely new underwriting process. Instead, lenders could adjust the loan value based on the new home price. Portable mortgages are already relatively common in Canada and the United Kingdom, where they’ve helped thousands of families sell their homes and buy new ones under their current mortgage terms.78

By preventing mortgage mobility, due-on-sale clauses perpetuate a lock-in effect whenever market rates surpass the fixed rates of existing mortgages — squeezing the housing supply and discouraging homeowners from moving or refinancing. Recent research shows that the likelihood of a home selling drops by 20% for each percentage point that mortgage rates rise above fixed rates.79 Studies also show that every $1,000 increase in annual mortgage costs reduces family mobility by about 12%, and that a 200-basis-point rise in interest rates corresponds to roughly a one-third lower probability of moving over the following eight years.80

The lock-in effect also inflates home prices and exacerbates economic inequality, as more affluent borrowers can better time their home sales strategically and absorb fluctuations in prices.81 When mortgage rates started to climb in 2022 after bottoming out at less than 3% during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, lock-in prevented an estimated 1.7 million home sale transactions and increased home prices by 7%.82

Mortgage mobility, on the other hand, can help alleviate this lock-in effect, freeing up existing housing supply and making it easier for families to move affordably and when they want — no matter the interest rate environment.83 Research shows that by allowing new home purchases at lower-than-market rates, assumable mortgages stimulate housing market activity and can even help mitigate the adverse labor market effects associated with reduced mobility. Similarly, portable mortgages can make it easier for families to relocate as their needs change, improving overall housing mobility.84 In the U.S., where approximately 16% of households, or roughly 21 million people, are empty nests and Baby Boomers own 28% of the nation’s largest homes, more affordable and flexible mortgage financing could free up millions of existing homes for younger buyers or large families.85

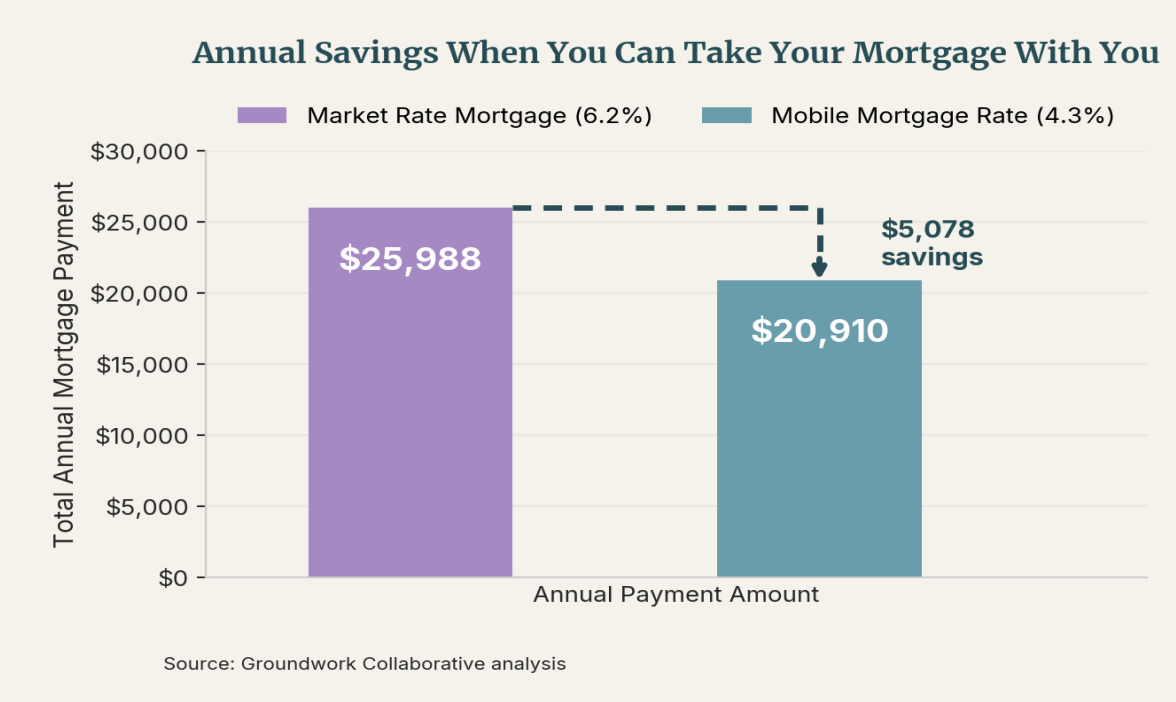

Mortgage mobility can also save families money. For example, if a family buying a median-priced $429,400 home could use the lower 4.3% rate that many current homeowners already have, instead of taking out a new mortgage at today’s 6.24% rate, they would save roughly $5,000 a year.86

Although a handful of private companies have recently begun offering mobile mortgage financing in the limited situations where it is already permitted under federal law, policymakers can do their part to unlock access by, first and foremost, eliminating the federal due-on-sale clause pre-emption in the Garn–St. Germain Act (12 U.S. Code § 1701j-3).87 Doing so would remove one of the key roadblocks to scaling conventional mortgage mobility.

However, revoking the due-on-sale prohibition pre-emption would not, on its own, enable wider uptake: States could still pass their own laws requiring or banning automatic due-on-sale clauses. To ensure mobile mortgage financing is available to borrowers who want it, Congress can include language that explicitly requires lenders to permit mortgage assumption and portability when requested by both buyer and seller, subject to existing creditworthiness and underwriting requirements. Additionally, to ensure that using a portable mortgage, in particular, wouldn’t trigger a full repayment, Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and FHA can amend their securitization standards such that changing the collateral of a loan (i.e., porting a mortgage from one home to another) is not considered a violation of investor contracts on the secondary market.88

Policymakers can also expand the option for mobile financing for the government-backed loans — from FHA, VA, and USDA — already eligible for it by eliminating requirements for lender approval. Other credit and income requirements that assess borrower repayment capacity could remain in place. Doing so would require an Act of Congress for VA loans (38 U.S.C. § 3714), but easing these restrictions for FHA (24 C.F.R. § 203.512) and USDA (7 C.F.R. § 3550.163) loans could be done through rule changes.89 To account for the transaction costs that lenders incur when transferring mortgages, FHA and VA can also raise the cap that servicers can charge — currently set at $1,800 for FHA loans and a base amount of $250 for VA loans.90 Conventional mortgage lenders aren’t bound by a cap and often charge between 0.5% and 1% of the loan amount.91

Additionally, because mortgage portability, in particular, primarily benefits families who already have low rates, it would have limited effect on expanding or equalizing access to homeownership. To blunt this disproportional impact, Congress could set limitations on how many times a homeowner (in the case of portables) or a property (in the case of assumables) can utilize a mobile mortgage. It could also ensure that such financing options apply only to forward mortgages.

Expanding mortgage financing is not a fix-all for the U.S.’s housing affordability crisis, as it is only an advantageous tool when interest rates are high and will not resolve the urgent issues facing millions of renters overburdened by high rents, shrinking options, and exploitative landlords.92 Moreover, enabling more mobile mortgages will not mean every family who wants to utilize one can. Mortgage mobility does not reduce the upfront cost of home purchase and borrowers may still need to secure second mortgages to finance down payments.93 But mobile mortgages can help free up existing housing stock and meaningfully reduce recurring monthly costs, making home ownership more affordable and sustainable for families into the future.

Enabling Government Issued Low-Rate Mortgages Directly to Consumers

Perhaps the most direct role for the federal government in the mortgage market is to extend the government’s low cost of borrowing to prospective homebuyers by directly financing mortgages at lower rates than commercial lenders.

Private lenders attach a spread to the cost of borrowing to hedge the risk of issuing the loan (like the potential for default or early refinancing if rates fall) and the reduced liquidity of mortgage-backed securities compared to other kinds of holdings. The 30-year fixed mortgage — the most popular mortgage product in the U.S. — is benchmarked to the 10-year Treasury yield. Historically, lenders have added a spread of roughly 1.8%.94 Since 2020 it’s been roughly 2.3%. Depending on the total value of the loan, this add-on can cost families tens of thousands of dollars over the lifetime of their mortgage.

Instead, the federal government could provide direct loans to consumers at (or close to) the cost of borrowing, thereby saving families thousands of dollars each year. Doing so would extend the benefits of the government’s cheaper financing directly to consumers. To ensure that the program targets the low- and middle-income homeowners who are most likely to need and benefit from cheaper financing, awards could be pegged to the median purchase price of single-family homes in any given area. Income and credit thresholds could also be established, as they already are for government-backed mortgages, to allow for more efficient underwriting.

This would be a more effective use of government support than the indirect policy lever of the Mortgage Interest Deduction (MID). Though the MID is the federal government’s primary mechanism for offsetting high mortgage costs for borrowers, it disproportionately benefits the higher-income households who are more likely to itemize deductions.95 It also drives up house prices and encourages construction of larger and more expensive homes, while having no effect on homeownership for new buyers or delivering any meaningful benefit to low- or middle-income households.96

The federal government could finance these direct loans without necessarily servicing them (i.e., conducting the customer-facing activities like collecting payments and handling defaults and foreclosures). Indeed, federal student loan programs have a similar structure: The government finances student loans but private firms compete for contracts to service them for consumers. That system, reliant on third-party contractors as middlemen, has considerable downsides — especially for the millions of borrowers who must contend with unaccountable practices and abuses by student loan servicers each with their own websites, customer service lines, and inquiry and resolution processes.97 This arrangement is a rare example of the federal government directly financing, but not servicing, loans.

Alternatively, the federal government can act as both lender and servicer. It already does so in the vast majority of instances in which agencies operate direct loan programs. This is how both the NADL program and USDA’s Section 502 Direct Loans function, as do the Small Business Administration’s Economic Injury Disaster Loans, the Department of Energy’s Innovative Energy Loan Guarantee Program and Advanced Technology Vehicles Manufacturing Direct Loan Program, and the Department of Transportation’s Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act Direct Loan program. While building out this capacity at the federal housing agencies to accommodate direct mortgage lending at scale would require investing in agency infrastructure and staffing, it would not require the government to take on dramatically different functions or conduct dramatically different activities than it has historically.

Enhancing Consumer Transparency in the Mortgage Market

Policymakers can also enhance consumer protections to ensure that navigating the mortgage market is safe and straightforward for consumers.

Since the onus of finding and securing the “best” mortgage is on the consumer, many — especially first-time homebuyers without experience in this complicated marketplace — simply fail to pursue better financing alternatives.98 The CFPB has found that more than 30% of borrowers do not comparison-shop for their mortgage, and more than 75% apply for a mortgage at only one lender.99 Going with the first or only lender a borrower checks out — regardless of if they offer the more competitive terms — costs the average homebuyer approximately $300 per year and many thousands of dollars over the life of a loan.100

Even if borrowers have the resources to research different mortgage offers, the systemic lack of transparency in rates and terms creates opportunity for lenders to collude and drive up prices. A recently filed federal class-action lawsuit alleges that dozens of major lenders, including mega-players like Wells Fargo, Rocket Mortgage, and JP Morgan Chase, used analytics software to share proprietary, real-time pricing information and coordinate mortgage rates.101

Policymakers can alleviate this time and energy burden for consumers by creating a centralized online platform where all lenders must list their terms, fees, eligibility requirements, and customer service information. Such a platform could bring closely-held industry information out of the shadows, equipping consumers with the knowledge necessary to navigate the mortgage market successfully. The CFPB, already responsible for overseeing mortgage servicers, is well-positioned to provide and maintain this platform.

Conclusion

The federal government has the potential to play an affirmatively market-shaping role in the mortgage market, reducing costs for borrowers and improving accessibility to financing for families. While no single reform will completely resolve the widespread housing affordability crisis in the U.S., federal measures to lower mortgage insurance costs, expand access to mobile loan products, issue low-rate direct loans, and enhance consumer protections are an opportunity for the federal government to come off the sidelines and shape the mortgage market in service of American families.

By leveraging the government’s unique financing power and regulatory authority to craft a mortgage system that is simpler, less costly, and more responsive to households’ needs, millions of families who feel buying a home is out of reach may finally be able to achieve and maintain homeownership.

Author Bios

Emily DiVito is the Senior Advisor for Economic Policy at Groundwork Collaborative. Prior to Groundwork, she was the Director for Finance, Corporate Regulation, and Consumer Protection at the Roosevelt Institute and a policy advisor at the U.S. Treasury Department. Emily has a BA from Wellesley College and an MPA from Columbia University.

Bharat Ramamurti served as Deputy Director of the National Economic Council and Advisor for Strategic Economic Communications in the Biden-Harris administration. In that role, he helped shape the administration’s economic message, worked with Congress to secure the enactment of several landmark pieces of economic legislation, and helped lead the administration’s efforts on student debt, competition policy, broadband, artificial intelligence, social media platforms, financial regulation, and more. Before joining the administration, he was appointed as a Member of the Congressional Oversight Commission for the CARES Act by Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer. He previously served as the top banking and economic policy advisor for Senator Elizabeth Warren, including during her presidential campaign. He is a graduate of Harvard College and Yale Law School.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Agatha Pinheiro, Nia Law, Alex Jacquez, Breyon Williams, and Imari Stewart for research assistance, insights, and feedback. Carol McCarthy provided editorial support.

Endnotes

[1] Jeff Ostrowski, Study: Six-Figure Income Needed To Afford Home In More Than Half Of U.S. (Bankrate, 2025), https://www.bankrate.com/real-estate/home-affordability-in-current-housing-market-study/.

[2] “WSFS Mortgage Regional Study Finds Homebuyers Feel High Levels of Anxiety When Buying a Home, Prefer Personal Touch and Guidance From Someone They Can Trust,” WSFS Bank, June 17, 2020, https://investors.wsfsbank.com/news-and-events/press-releases/press-releases-details/2020/WSFS-Mortgage-Regional-Study-Finds-Homebuyers-Feel-High-Levels-of-Anxiety-When-Buying-a-Home-Prefer-Personal-Touch-and-Guidance-From-Someone-They-Can-Trust-06-17-2020/default.aspx.

[3] Nick Lichtenberg, “Trump’s 50-Year Mortgage Would Save You about $119 a Month While Doubling the Interest You Pay over the Long Run, UBS Estimates,” Fortune, November 12, 2025, https://fortune.com/2025/11/12/how-much-would-50-year-morgage-save-per-month-ubs/; Sophia Cai and Dasha Burns, “‘Sold POTUS a Bill of Goods’: White House Furious with Pulte over 50-Year Mortgage,” POLITICO, November 10, 2025, https://www.politico.com/news/2025/11/10/trumps-50-year-mortgage-plan-is-getting-panned-allies-blame-this-man-00645654;

[4] Bharat Ramamurti, Seven Key Questions About the Potential Release of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac from Government Conservatorship (American Economic Liberties Project, n.d.), accessed November 17, 2025, https://www.economicliberties.us/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Fannie-and-Freddie-Piece-5.25-FINAL.pdf; There’s No Place Like Home: How Trump Is Making Housing Unaffordable (Groundwork Collaborative, 2025), 1-5, https://cdn.sanity.io/files/ifn0l6bs/production/2939e14dbf592f87823862f069ffe6fd21b988ee.pdf.

[5] Samantha Delouya, “The Trump Administration Is ‘Actively Evaluating’ Portable Mortgages. What You Need to Know,” CNN, November 13, 2025, https://www.cnn.com/2025/11/13/homes/portable-mortgages-what-to-know.

[6] Ganesh Sitaraman and Christopher Serkin, “Post-Neoliberal Housing Policy,” SSRN Scholarly Paper 5227899 (Social Science Research Network, April 23, 2025), https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5227899.

[7] Bianca Werner and Roger Tufts, The History of National Bank Real Estate Lending: Part I (1863-1980), Moments in History (Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, 2023), https://www.occ.gov/publications-and-resources/publications/economics/moments-in-history/pub-moments-in-history-real-estate-lending-part1.pdf.

[8] Life insurance companies and mutual savings banks were also active lenders, but regulations often prevented them from lending across state lines or beyond certain distances from their physical location.

Bianca Werner and Roger Tufts, The History of National Bank Real Estate Lending: Part I (1863-1980), Moments in History (Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, 2023), https://www.occ.gov/publications-and-resources/publications/economics/moments-in-history/pub-moments-in-history-real-estate-lending-part1.pdf; Matthew Wells, “A Short History of Long-Term Mortgages,” Econ Focus (First Quarter 2023): 18–22, https://www.richmondfed.org/publications/research/econ_focus/2023/q1_economic_history.

[9] Sebastián Fleitas et al., “The U.S. Postal Savings System and the Collapse of B&Ls During the Great Depression,” Working Paper 30609 (National Bureau of Economic Research, October 2022), https://doi.org/10.3386/w30609.

[10] Jonathan Rose and Kenneth A. Snowden, “The New Deal and the Origins of the Modern American Real Estate Loan Contract,” Working Paper 18388 (National Bureau of Economic Research, September 2012), https://doi.org/10.3386/w18388.

[11] “Brother, Can You Spare A Billion? The Story of Jesse H. Jones: Jesse Jones,” PBS, April 2000, https://www.pbs.org/jessejones/jesse_greatdepression_1.htm; David C. Wheelock, “Regulation, Market Structure and the Bank Failures of the Great Depression,” Review (Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis), no. March/April (1995): 27–38, https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/files/docs/meltzer/whereg95.pdf.

[12] In 1925, new home construction peaked at 937,000 new units. By 1933, the number l had plummeted to 93,000 units, and the 1925 peak was not reached again until the end of World War II.

Bureau of Labor Statistics, “UNEMP. RATE – Civilian labor force 14 yrs. & over,” accessed November 17, 2025, https://data.bls.gov/timeseries/LFU22000100; Kenneth Snowden et al., “Collateral Damage: Foreclosures and New Mortgage Lending in the 1930s,” VoxEU.org, January 18, 2019, https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/collateral-damage-foreclosures-and-new-mortgage-lending-1930s; Richard K. Green and Susan M. Wachter, “The American Mortgage in Historical and International Context,” SSRN Scholarly Paper 908976 (Social Science Research Network, June 14, 2006), https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=908976; Tom Nicholas and Anna Scherbina, Real Estate Prices During the Roaring Twenties and the Great Depression, 41, no. 2 (2013): 278–309, https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=41283.

[13] A Brief History of the Housing Government-Sponsored Enterprises (Federal Home Finance Agency Office of Inspector General), 1–9, https://www.fhfaoig.gov/Content/Files/History%20of%20the%20Government%20Sponsored%20Enterprises.pdf.

[14] Wells, “A Short History of Long-Term Mortgages,” https://www.richmondfed.org/publications/research/econ_focus/2023/q1_economic_history.

[15] Though the HOLC operated until 1954, it primarily focused on collecting payments on existing loans.

Price V. Fishback et al., “New Evidence on Redlining by Federal Housing Programs in the 1930s,” Working Paper 29244 (National Bureau of Economic Research, September 2021), https://doi.org/10.3386/w29244.

[16] The HOLC is also widely associated with the racist practice of redlining. Its infamous residential security maps, which gave neighborhoods a grade based on their “desirability,” were used as a discriminatory tool for lenders to deny credit to people living and real estate developers seeking to build in “undesirable” areas.

Brandon Donnelly, “A Short History of Redlining,” Sustainable Cities Collective, https://www.smartcitiesdive.com/ex/sustainablecitiescollective/short-history-redlining/1162160/; Bruce Mitchell and Juan Franco, HOLC “Redlining” Maps: The Persistent Structure of Segregation and Economic Inequality NCRC (National Community Reinvestment Coalition, 2018), https://ncrc.org/wp-content/uploads/dlm_uploads/2018/02/NCRC-Research-HOLC-10.pdf; Wells, “A Short History of Long-Term Mortgages,” https://www.richmondfed.org/publications/research/econ_focus/2023/q1_economic_history.

[17] Fishback et al., “New Evidence on Redlining by Federal Housing Programs in the 1930s,” https://doi.org/10.3386/w29244.

[18] Fishback et al., “New Evidence on Redlining by Federal Housing Programs in the 1930s,” https://doi.org/10.3386/w29244.

[19] Background and History (Federal National Mortgage Association, 1975), 1–70, https://fcic-static.law.stanford.edu/cdn_media/fcic-docs/1975-00-00%20FNMA%20–%20History.pdf.

[20] Fannie Mae initially only purchased FHA-backed loans. In 1948, it began purchasing VA loans. In 1954, Congress transitioned Fannie Mae into a public-private, mixed ownership corporation before converting it to private ownership in 1968. In 1970, Congress authorized Fannie Mae to buy conventional mortgages, and it issued its first mortgage-backed security (MBS) sale in the secondary market in 1981.

A Brief History of the Housing Government-Sponsored Enterprises, https://www.fhfaoig.gov/Content/Files/History%20of%20the%20Government%20Sponsored%20Enterprises.pdf; “Fannie Mae Charter,” Fannie Mae, July 25, 2019, https://www.fanniemae.com/about-us/corporate-governance/fannie-mae-charter; John J. McConnell and Stephen A. Buser, “The Origins and Evolution of the Market for Mortgage-Backed Securities,” Annual Review of Financial Economics 3, no. Volume 3, 2011 (2011): 173–92, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-financial-102710-144901.

[21] Green and Wachter, “The American Mortgage in Historical and International Context,” SSRN Scholarly Paper 908976 (Social Science Research Network, June 14, 2006), https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=908976.

[22] “Servicemen’s Readjustment Act (1944),” The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, September 22, 2021, https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/servicemens-readjustment-act.

[23] Matthew Wells, “A Short History of Long-Term Mortgages,” https://www.richmondfed.org/publications/research/econ_focus/2023/q1_economic_history.

[24] Matthew Wells, “A Short History of Long-Term Mortgages,” https://www.richmondfed.org/publications/research/econ_focus/2023/q1_economic_history.

[25] “Servicemen’s Readjustment Act (1944),” https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/servicemens-readjustment-act.

[26] Daniel K. Fetter, “The Twentieth-Century Increase in U.S. Home Ownership: Facts and Hypotheses,” in Housing and Mortgage Markets in Historical Perspective (University of Chicago Press, 2014), https://www.nber.org/books-and-chapters/housing-and-mortgage-markets-historical-perspective/twentieth-century-increase-us-home-ownership-facts-and-hypotheses.

[27] Fetter, “The Twentieth-Century Increase in U.S. Home Ownership: Facts and Hypotheses,” https://www.nber.org/books-and-chapters/housing-and-mortgage-markets-historical-perspective/twentieth-century-increase-us-home-ownership-facts-and-hypotheses.

[28] According to Fetter (2014), veteran status and eligibility for VA home loan programs accounts for roughly 7.4% of the overall increase in homeownership between 1940 and 1960.

[29] Fetter, “The Twentieth-Century Increase in U.S. Home Ownership: Facts and Hypotheses” https://www.nber.org/books-and-chapters/housing-and-mortgage-markets-historical-perspective/twentieth-century-increase-us-home-ownership-facts-and-hypotheses.

[30] Comparatively, new privately-owned housing starts were just over 1.3 million as of August 2025, though the U.S. population is more than double the 1950 level.

Barbara T. Alexander, “The U.S. Homebuilding Industry: A Half-Century of Building the American Dream,” John T. Dunlop Lecture (Harvard University), Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies, October 12, 2000, 1–44, https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/dl-transcript/m00-1_alexander.pdf; Brian Potter, “WW2 Era Mass-Produced Housing (Part 1),” Construction Physics, May 3, 2024, https://www.construction-physics.com/p/ww2-era-mass-produced-housing-part; U.S. Census Bureau and U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, “New Privately-Owned Housing Units Started: Total Units,” HOUST, FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis;, September 17, 2025, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/HOUST.

[31] A Brief History of the Housing Government-Sponsored Enterprises, https://www.fhfaoig.gov/Content/Files/History%20of%20the%20Government%20Sponsored%20Enterprises.pdf.

[32] Despite these measures, the thrift industry collapsed in the 1980s — after a series of high-profile scandals at S&Ls and the Reagan administration’s deregulatory measures — encouraged riskier behavior;

Fred E Case, “Deregulation: Invitation to Disaster in the S&L Industry,” Fordham Law Review 59, no. 6 (1991), https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2923&context=flr; Ramon DeGennaro and James B. Thomson, “Capital Forbearance And Thrifts: An Ex Post Examination Of Regulatory Gambling,” Working Paper, nos. 92–09 (September 1992), https://doi.org/10.26509/frbc-wp-199209; Richard W. Stevenson, “California’s Daring Thrift Unit,” Business, The New York Times, May 25, 1987, https://www.nytimes.com/1987/05/25/business/california-s-daring-thrift-unit.html.

[33] A Brief History of the Housing Government-Sponsored Enterprises, https://www.fhfaoig.gov/Content/Files/History%20of%20the%20Government%20Sponsored%20Enterprises.pdf.

[34] N Eric Weiss and Michael V Seitzinger, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac: A Legal and Policy Overview, CRS Report for Congress (Congressional Research Service, 2008), https://www.everycrsreport.com/files/20080228_RL33756_3c18d20f2066829f52d8a7589cbf585c62871787.pdf.

[35] A Brief History of the Housing Government-Sponsored Enterprises, https://www.fhfaoig.gov/Content/Files/History%20of%20the%20Government%20Sponsored%20Enterprises.pdf; Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, “Origins of the Crisis,” in Crisis and Response: An FDIC History, 2008–2013 (Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, 2018), https://www.fdic.gov/media/18636#:~:text=A%20number%20of%20the%20new,Brookings%20Papers%20on;

[36] John V. Duca, “Subprime Mortgage Crisis,” Federal Reserve History, November 22, 2013, https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/subprime-mortgage-crisis.

[37] Adam Looney and Michael Greenstone, Unemployment and Earnings Losses: The Long-Term Impacts of the Great Recession on American Workers (The Hamilton Project, 2011), https://www.hamiltonproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/110411_jobs_greenstone_looney.pdf; Andrew Haughwout, et al., “How Are They Now? A Checkup on Homeowners Who Experienced Foreclosure,” Liberty Street Economics, May 8, 2024, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2024/05/how-are-they-now-a-checkup-on-homeowners-who-experienced-foreclosure/; National Economic Council et al., The Financial Crisis: Five Years Later (Executive Office of the President, 2013), 1–49, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/docs/20130915-financial-crisis-five-years-later.pdf.

[38] “Outstanding Residential Mortgage Statistics,” National Mortgage Database, October 17, 2025, https://www.fhfa.gov/data/dashboard/nmdb-outstanding-residential-mortgage-statistics.

[39] Loans for housing and buildings on adequate farms, 42 U.S. Code § 1472, https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/42/1472; “Native American Direct Loan,” US Department of Veterans Affairs, August 15, 2024, https://www.va.gov/housing-assistance/home-loans/loan-types/native-american-direct-loan/; “Single Family Housing Direct Home Loans,” Rural Development US Department of Agriculture, January 5, 2015, https://www.rd.usda.gov/programs-services/single-family-housing-programs/single-family-housing-direct-home-loans.

[40] USDA Rural Development Housing Activity Report – Fiscal Year 2024 (Housing Assistance Council, 2025), https://ruralhome.org/usda-rural-development-housing-activity-report-fiscal-year-2024/.

[41] U.S. Government Accountability Office, Native American Veterans: Improvements to VA Management Could Help Increase Mortgage Loan Program Participation, GAO-22-104627 (2022), 1–79, https://www.gao.gov/assets/d22104627.pdf.

[42] Ryan Murray, “Mortgage Broker Market Share,” Murray Mortgage Solutions, accessed November 18, 2025, https://www.murraymortgagesolutions.com/leaning-center/mortgage-broker-market-share.

[43] Flávia Furlan Nunes, “UWM Moves to Dismiss Steering Claims, Cites Benefit to ‘Market Speculators,’” Mortgage, HousingWire, June 24, 2024, https://www.housingwire.com/articles/uwm-moves-to-dismiss-steering-claims-cites-benefit-to-market-speculators/.

[44] Flávia Furlan Nunes, “Growing Mortgage Brokerages Are under More CFPB Scrutiny,” Mortgage, HousingWire, November 6, 2025, https://www.housingwire.com/articles/mortgage-brokerages-cfpb-regulations-wholesale-lending/.

[45] “CFPB Files Lawsuit to Stop Illegal Kickback Scheme to Steer Borrowers to Rocket Mortgage,” Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, December 23, 2024, https://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/newsroom/cfpb-files-lawsuit-to-stop-illegal-kickback-scheme-to-steer-borrowers-to-rocket-mortgage/.

[46] “News Releases: Yost Sues Wholesale Mortgage Lender Over Deceptive Business Practices,” Dave Yost Ohio Attorney General, April 17, 2025, https://www.ohioattorneygeneral.gov/Media/News-Releases/April-2025/Yost-Sues-Wholesale-Mortgage-Lender-Over-Deceptive.

[47] State of Ohio Rel. Dave Yost Ohio Attorney General v United Wholesale Mortgage LLC, 205520547 (Court of Common Pleas), https://www.ohioattorneygeneral.gov/Files/Briefing-Room/News-Releases/2025-4-16-UWM-Complaint-Filed.aspx.

[48] “WSFS Mortgage Regional Study Finds Homebuyers Feel High Levels of Anxiety When Buying a Home, Prefer Personal Touch and Guidance From Someone They Can Trust,” https://investors.wsfsbank.com/news-and-events/press-releases/press-releases-details/2020/WSFS-Mortgage-Regional-Study-Finds-Homebuyers-Feel-High-Levels-of-Anxiety-When-Buying-a-Home-Prefer-Personal-Touch-and-Guidance-From-Someone-They-Can-Trust-06-17-2020/default.aspx.

[49] America’s Rental Housing 2024 (Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, 2024), 1-56, https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/reports/files/Harvard_JCHS_Americas_Rental_Housing_2024.pdf.

[50] Federal mortgage programs administered by the VA and USDA have different requirements for mortgage insurance. VA loans do not require an MIP but instead require a one-time VA funding fee (typically 1.25% 3.3% depending on down payment amount and if the borrower is a first-time homeowner). USDA loans require a guarantee fee (currently calculated as 3% upfront, plus 0.55% in annual fee) paid for the lifetime of the loan, which cannot be eliminated with refinancing.

“Business & Industry Loan Guarantees,” Rural Development US Department of Agriculture, https://www.rd.usda.gov/programs-services/business-programs/business-industry-loan-guarantees; “VA Funding Fee and Loan Closing Costs,” US Department of Veterans Affairs, April 4, 2025, https://www.va.gov/housing-assistance/home-loans/funding-fee-and-closing-costs/.

[51] The UFMIP, typically calculated as 1.75% of the base loan amount, is usually due when a borrower closes on their FHA loan. Alternatively, it can be added to the balance of the loan. A borrower only pays it once unless they refinance or take on another FHA loan. The annual MIP, typically 0.55%, can be paid in equal monthly installments.

“Single Family Mortgage Insurance Premiums,” U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, accessed November 18, 2025, https://www.hud.gov/hud-partners/housing-mip.

[52] Payment amounts can range from 0.2% to 2.25% of the loan amount paid monthly. Nearly 40 million borrowers have had to take out PMI since 1957 when the PMI firm, Mortgage Guaranty Insurance Corporation, was founded as an alternative to FHA insurance.

“Press Release: New Report: 800,000 Low Down Payment Borrowers Purchased Homes in 2024 with Private Mortgage Insurance,” USMI, August 6, 2025, https://www.usmi.org/press-release-new-report-800000-low-down-payment-borrowers-purchased-homes-in-2024-with-private-mortgage-insurance/.

[53] John Walsh et al., Mortgage Insurance Data At A Glance – 2023 (Urban Institute, 2023), https://www.urban.org/research/publication/mortgage-insurance-data-glance-2023.

[54] “Single Family Mortgage Insurance Premiums,” https://www.hud.gov/hud-partners/housing-mip; What Do Prospective Homebuyers Know about Mortgages and Mortgage Shopping?, 3, Know Before You Owe: Mortgage Shopping Study (Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, 2018), 1–18, https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/bcfp_mortgages_shopping-study_brief-3-knowledge.pdf; “What Is Mortgage Insurance and How Does It Work?,” Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, May 14, 2024, https://www.consumerfinance.gov/ask-cfpb/what-is-mortgage-insurance-and-how-does-it-work-en-1953/.

[55] Sarah Schlichter, “The Average Home Insurance Cost in the U.S. for 2025,” NerdWallet, May 1, 2025, https://www.nerdwallet.com/article/insurance/average-homeowners-insurance-cost.

[56] “What Is an FHA Mortgage Insurance Premium (MIP)?,” Rocket Mortgage, https://www.rocketmortgage.com/learn/fha-mortgage-insurance-premium.

[57] U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Housing–Federal Housing Commissioner, Mortgagee Letter 2023-05, February 22, 2023, https://archives.hud.gov/news/2023/2023-05hsgml.pdf.

[58] Regarding the Financial Status of the Federal Housing Administration Mutual Mortgage Insurance, Annual Report to Congress (Federal Housing Administration), 1–132, https://www.hud.gov/sites/dfiles/Housing/documents/2024FHAAnnualReportMMIFund.pdf.

[59] During his first term, President Donald Trump reversed an Obama Administration plan to lower MIP payments that would have saved FHA-insured homeowners an average of $500 per year, though Trump has proposed reducing MIP payments for developers’ multifamily housing purchases to a uniform 0.25% — down from 0.70%.

Daniel Burns and Sarah N. Lynch, “One of Trump Administration’s First Actions Suspended a Controversial Plan That Would’ve Saved Some Homeowners $500,” Markets, Business Insider, January 20, 2017, https://www.businessinsider.com/trump-administration-fha-premiums-2017-1; Proposed Changes in Mortgage Insurance Premiums Applicable to FHA Multifamily Insurance Programs,” Federal Register 90 (June 26, 2025): 27332, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2025/06/26/2025-11814/proposed-changes-in-mortgage-insurance-premiums-applicable-to-fha-multifamily-insurance-programs.

Regarding the Financial Status of the Federal Housing Administration Mutual Mortgage Insurance, https://www.hud.gov/sites/dfiles/Housing/documents/2024FHAAnnualReportMMIFund.pdf.

[60] General Surplus and Participating Reserve Accounts, 12 U.S. Code § 1711, https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/12/1711; Katie Jones, FHA Single-Family Mortgage Insurance: Financial Status of the Mutual Mortgage Insurance Fund (MMI Fund), R42875 (Congressional Research Service, 2022), https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R42875; Regarding the Financial Status of the Federal Housing Administration Mutual Mortgage Insurance, https://www.hud.gov/sites/dfiles/Housing/documents/2024FHAAnnualReportMMIFund.pdf;

[61] Alex Roha, “FHA Commissioner on the MMI Fund Capital Ratio Growth to 6.1%,” Mortgage, HousingWire, November 14, 2025, https://www.housingwire.com/articles/fha-commissioner-on-the-mmi-fund-capital-ratio-growth-to-6-1/.

[62] Amalie Zinn et al., “Gutting the FHA Will Decrease Housing Market Efficiency and Hurt Borrowers,” Urban Wire, Urban Institute, February 26, 2025, https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/gutting-fha-will-decrease-housing-market-efficiency-and-hurt-borrowers.

[63] “Mortgage Insurance for Conventional and FHA Loans,” FHA.com, June 27, 2025, https://www.fha.com/fha_article?id=4064.

[64] “When Can I Remove Private Mortgage Insurance (PMI) from My Loan?,” Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, August 28, 2023, https://www.consumerfinance.gov/ask-cfpb/when-can-i-remove-private-mortgage-insurance-pmi-from-my-loan-en-202/.

[65] Lorelei Salas, “Seven Examples of Unfair Practices and Other Violations by Mortgage Servicers: CFPB Supervision Activities Uncover Red Flags,” Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, December 9, 2021, https://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/blog/seven-examples-unfair-practices-and-other-violations-mortgage-servicers-cfpb-supervision-activities-uncover-red-flags/.

[66] Though the National Housing Act of 1938 (12 U.S.C. § 1711(f)(2)) requires the capital ratio of the Mutual Mortgage Insurance Fund — the fund that acts as the insurer of FHA-backed mortgages — to be at least 2%, it is currently more than 5 times that at roughly 11.5%. MIP protect lenders (you could say something like – and btw lenders are already overprotected by a more than healthy fund due to charging so much from folks).

General Surplus and Participating Reserve Accounts, 12 U.S. Code § 1711, https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/12/1711; Katie Jones, FHA Single-Family Mortgage Insurance: Financial Status of the Mutual Mortgage Insurance Fund (MMI Fund), https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R42875; Regarding the Financial Status of the Federal Housing Administration Mutual Mortgage Insurance, https://www.hud.gov/sites/dfiles/Housing/documents/2024FHAAnnualReportMMIFund.pdf; Termination of private mortgage insurance, 12 U.S. Code § 4902, https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/12/4902.

[67] Free assumability; exceptions, 24 CFR § 203.512, https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/24/203.512.

[68] Sheharyar Bokhari and Dana Anderson, “Empty Nesters Own Twice As Many Large Homes As Millennials With Kids,” Redfin News, January 16, 2024, https://www.redfin.com/news/empty-nesters-own-large-homes/; “The Outlook for US Housing Supply and Affordability,” Goldman Sachs, October 21, 2025, https://www.goldmansachs.com/insights/articles/the-outlook-for-us-housing-supply-and-affordability.

[69] During this time, assumable (conventional) mortgages were allowable under federal law at the discretion of the lender. financial capacity and state law).

[70] “The Due-on-Sale Controversy: Beneficial Effects of the Garn-St. Germain Depository Institution Act of 1982,” Duke Law Journal 33, no. 1 (1984): 121–40, https://scholarship.law.duke.edu/dlj/vol33/iss1/3/.

[71] “The Due-on-Sale Controversy: Beneficial Effects of the Garn-St. Germain Depository Institution Act of 1982,” https://scholarship.law.duke.edu/dlj/vol33/iss1/3/.

[72] Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, “Federal Funds Effective Rate,” FEDFUNDS, FRED, November 3, 2025, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/FEDFUNDS; Freddie Mac, “30-Year Fixed Rate Mortgage Average in the United States,” MORTGAGE30US, FRED, November 13, 2025, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/MORTGAGE30US.

[73] Michael LaCour-Little et al., “Assumable Financing Redux: A New Challenge for Appraisal?,” SSRN Scholarly Paper 3418449 (Social Science Research Network, July 11, 2019), https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3418449.

[74] In 1975, Fred and Dorothy Man tried to let Cynthia Wellenkamp purchase their home and assume their 8% mortgage in a 9.25% market. Bank of America, which held the mortgage, initiated proceedings against Wellenkamp to enforce a due-on-clause provision and force her to take out a new loan.

LaCour-Little et al., “Assumable Financing Redux: A New Challenge for Appraisal?,” https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3418449; Wellenkamp v. Bank of America, 21 Cal. 3d 943 (Cal. 1978), https://law.justia.com/cases/california/supreme-court/3d/21/943.html.

[75] Around this time, six state courts (AZ, AR, CA, MI, MS, and WA) and six other state legislatures (CO, GA, IA, MN, NM, and UT) restricted enforcement of due-on-sale clauses in mortgage contracts;

“The Due-on-Sale Controversy: Beneficial Effects of the Garn-St. Germain Depository Institution Act of 1982,” https://scholarship.law.duke.edu/dlj/vol33/iss1/3/.

[76] Garn-St Germain Depository Institutions Act of 1982, 97–320, Congress 97, 96 (1982), https://www.congress.gov/97/statute/STATUTE-96/STATUTE-96-Pg1469.pdf.

[77] There are several exceptions to a lender’s ability to enforce due-on-sale provisions in conventional mortgages, including if the original homebuyer(s) go through a divorce or legal separation, transfers the property to their children, or transfers the property to a relative in the event of death or to a living trust. However, even in these instances, the CFPB has found that lenders often deceive or pressure borrowers into refinancing, overcharge, or delay to prevent timely mortgage assumption.

Homeowners Face Problems with Mortgage Companies after Divorce or Death of a Loved One, Issue Spotlight (Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, 2024), https://www.consumerfinance.gov/data-research/research-reports/homeowners-face-problems-with-mortgage-companies-after-divorce-or-death-of-a-loved-one/; Preemption of due-on-sale prohibitions, 12 U.S.C 12, § 1701j-3, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2020-title12/pdf/USCODE-2020-title12-chap13-sec1701j-3.pdf.

[78] Gary Buswell, “Getting a Mortgage in the UK in 2025,” Expatica, July 10, 2025, https://www.expatica.com/uk/housing/buying/your-guide-to-uk-mortgages-747470/#fixed-rate-mortgage; “Mortgage Terms and Amortization,” Government of Canada, October 15, 2025, https://www.canada.ca/en/financial-consumer-agency/services/mortgages/mortgage-terms-amortization.html; Peter Coy, “The Case for Letting Mortgages Move With Us,” Opinion, The New York Times, May 6, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/05/06/opinion/portable-mortgage-loans-housing.html.

[79] Ross Batzer et al., “The Lock-In Effect of Rising Mortgage Rates,” preprint, 2024, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5021709.

[80] Fernando Ferreira et al., “Housing Busts and Household Mobility,” Journal of Urban Economics 68, no. 1 (2010): 34–45, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2009.10.007; John M. Quigley, “Interest Rate Variations, Mortgage Prepayments and Household Mobility,” The Review of Economics and Statistics 69, no. 4 (1987): 636–43, https://doi.org/10.2307/1935958.

[81] Batzer et al., “The Lock-In Effect of Rising Mortgage Rates,” https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5021709.

[82] Batzer et al., “The Lock-In Effect of Rising Mortgage Rates,” https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5021709.

[83] As of writing, economists expect mortgage rates, impacted by the 10-year Treasury yield, to remain above 6% through at least 2029.

Hal Bundrick, “Mortgage Rate Predictions for the next 5 Years: What Experts Say.,” Yahoo Finance, November 14, 2025, https://finance.yahoo.com/personal-finance/mortgages/article/mortgage-rate-predictions-for-the-next-5-years-what-experts-say-195826363.html.

[84] Antje Berndt et al., “Breaking the Lock-In Effect: How Assumable Mortgages Shape Housing Prices and Supply Dynamics,” SSRN Scholarly Paper 5064022 (Social Science Research Network, December 15, 2024), https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5064022.

[85] Bokhari and Anderson, “Empty Nesters Own Twice As Many Large Homes As Millennials With Kids,” https://www.redfin.com/news/empty-nesters-own-large-homes/; Orphe Divounguy, “A ‘Silver Tsunami’ Won’t Solve Housing Affordability Challenges,” Zillow, December 5, 2024, https://www.zillow.com/research/empty-nesters-affordability-34636/.

[86] Assumes the homeowner has an existing 30-year mortgage at the average active mortgage rate of 4.3% would otherwise need to apply for a new loan at the current average 30-year fixed rate of 6.2% and that both the existing home and new home are at the median home price of $429,400. Also assumes that the homeowner puts 18% down is responsible for mortgage insurance of 0.5%. This estimate is not meant to represent potential savings for every family who may want to utilize mobile mortgages, nor does it fully capture all other costs incurred when moving and transferring a loan, including any additional fees or taxes levied.

Freddie Mac, “30-Year Fixed Rate Mortgage Average in the United States,” MORTGAGE30US, FRED, November 13, 2025, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/MORTGAGE30US.

“Aggregate Statistics,” National Mortgage Database, https://www.fhfa.gov/data/nmdb.

“Three out of Four Metro Areas Posted Home Price Increases in Second Quarter of 2025,” National Association of Realtors, August 12, 2025, https://www.nar.realtor/newsroom/three-out-of-four-metro-areas-posted-home-price-increases-in-second-quarter-of-2025.

Abby Badach Doyle, “What’s the Average Down Payment on a House?,” Nerdwallet, March 6, 2025, https://www.nerdwallet.com/mortgages/learn/average-down-payment-on-a-house. (edited)

[87] One such company, Roam, founded in 2023 when the average fixed rate mortgage was upwards of 7%, uses mortgage data and real estate listings to identify homes with FHA or VA loans that are eligible for assumption, and then facilitates the process for buyers for a 1% fee. Roam also partners with a lender to facilitate piggyback loans when buyers need them to shore up financing.

Amy Scott, “Assumable Mortgages Give Buyers a Second Chance at Low Rates,” Marketplace, September 23, 2024, 5:17, https://www.marketplace.org/story/2024/09/23/assumable-mortgages-give-buyers-a-second-chance-at-low-rates; Preemption of due-on-sale prohibitions, 12 U.S.C 12, § 1701j-3, https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/12/1701j-3; “Roam: Assumable Mortgage Homes Including VA & FHA Loans Listings,” accessed November 19, 2025, https://www.withroam.com/; Tara Siegel Bernard, “A Little-Known Way Home Buyers Can Beat High Mortgage Rates,” Business, The New York Times, May 9, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/05/09/business/low-rate-assumable-mortgage.html.

[88] Jiawei Zhang et al., “How Making Agency Mortgage-Backed Securities Portable May Impact Housing and Mortgage-Backed Securities Investors,” The Journal of Fixed Income 33, no. 3 (2024): 114–19, https://doi.org/10.3905/jfi.2023.1.176.

[89] Assumptions; release from liability, 38 U.S. Code § 3714, https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/38/3714; Free assumability; exceptions, 24 CFR § 203.512, https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/24/203.512; Transfer of security and assumption of indebtedness, 7 CFR § 3550.163. https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/7/3550.163.

[90] AssumeList, “FHA and VA Fee Update: Increased Allowances for Assumable Mortgages,” AssumeList, May 27, 2024, https://assumelist.com/blog/assumption-fee-update/; Ted Tozer, “Could a Rarely Used Government-Backed Loan Feature Help Level the Playing Field in Today’s High-Interest Housing Market?,” Urban Wire, Urban Institute, October 14, 2022, https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/could-rarely-used-government-backed-loan-feature-help-level-playing-field-todays-high.

[91] “Find What Is Assumption Fees in Real Estate Transactions,” SponsorCloud, accessed November 19, 2025, https://syndicationpro.com/glossary-definitions/assumption-fee.

[92] Mike Scarcella, “Greystar Agrees to $50 Million Settlement in RealPage Rental Pricing Lawsuit | Reuters,” Reuters, October 9, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/legal/government/greystar-agrees-50-million-settlement-realpage-rental-pricing-lawsuit-2025-10-02/; Sophia Wedeen, “Low-Cost Rentals Have Decreased in Every State,” Housing Perspectives, Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, July 6, 2023, https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/blog/low-cost-rentals-have-decreased-every-state; Sophia Wedeen et al., The Rent Eats More: Residual Income Housing Cost Burdens from 2019–2023 | Joint Center for Housing Studies (Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, 2025), 1–30, https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/research-areas/working-papers/rent-eats-more-residual-income-housing-cost-burdens-2019-2023.

[93] Indeed, research finds that some of the value of an assumable mortgage gets absorbed into the purchase price of the house, raising average property prices by as much as $20,000.

Berndt et al., “Breaking the Lock-In Effect: How Assumable Mortgages Shape Housing Prices and Supply Dynamics,” https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5064022.

[94] Calculated using FRED’s 30-Year Fixed Rate Mortgage Average in the United States and Market Yield on U.S. Treasury Securities at 10-Year Constant Maturity datasets.

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US), “Market Yield on U.S. Treasury Securities at 10-Year Constant Maturity, Quoted on an Investment Basis,” DGS10, FRED, November 19, 2025, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DGS10; Freddie Mac, “30-Year Fixed Rate Mortgage Average in the United States,” https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/MORTGAGE30US; Mitchell Hartman, “How 30-Year Fixed-Rate Mortgages Became the U.S. Standard,” Marketplace, June 17, 2025, https://www.marketplace.org/story/2025/06/17/how-30-year-fixed-rate-mortgages-became-the-us-standard; Nathaniel Drake, What Determines the Rate on a 30-Year Mortgage? (Fannie Mae, 2024), https://www.fanniemae.com/research-and-insights/publications/housing-insights/rate-30-year-mortgage.

[95] Megan McArdle, “What Any Economist Will Tell You (but No Real Estate Agent Will),” Opinion, The Washington Post, June 21, 2024, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2024/06/21/kill-mortgage-interest-deduction/; The Mortgage Interest Deduction: Options for Reform (The Budget Lab of Yale University, 2025), https://budgetlab.yale.edu/research/mortgage-interest-deduction-options-reform.

[96] William G. Gale, “Gutting the Mortgage Interest Deduction,” TaxVox, November 6, 2017, https://taxpolicycenter.org/taxvox/gutting-mortgage-interest-deduction; Jonathan Gruber et al., Do People Respond to the Mortgage Interest Deduction? Quasi-Experimental Evidence from Denmark, w23600 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2017), w23600, https://doi.org/10.3386/w23600.

[97] “Federal Loan Servicing Abuse,” Protect Borrowers, August 28, 2025, 4946, https://protectborrowers.org/what-we-do/federal-student-loans/federal-loan-servicing-abuse/.

[98] Consumers’ Mortgage Shopping Experience (Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, 2015), 1–26, https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201501_cfpb_consumers-mortgage-shopping-experience.pdf.

[99] Consumers’ Mortgage Shopping Experience, https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201501_cfpb_consumers-mortgage-shopping-experience.pdf.

[100] “Know Before You Owe: Mortgage Shopping Study,” Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, May 15, 2018, https://www.consumerfinance.gov/data-research/research-reports/know-before-you-owe-mortgage-shopping-study/.

[101] Brooklee Han, “Antitrust Lawsuit Targets Optimal Blue and Mortgage Lenders,” Legal, Mortgage, HousingWire, November 5, 2025, https://www.housingwire.com/articles/optimal-blue-antitrust-lawsuit/