Innovative Research /

Big Profits in Small Packages

Overview

Although inflation has come down considerably from its peak, prices remain elevated, and many Americans report significant levels of concern over high prices for essentials. Recent research from Groundwork Collaborative found that corporate profits drove over 50% of inflation during the second and third quarters of 2023.

Big Profits in Small Packages

Although inflation has come down considerably from its peak, prices remain elevated, and many Americans report significant levels of concern over high prices for essentials. Corporations have also experienced rising labor and input costs, but despite this, they’ve been able to maintain and even expand their profit margins to levels well above historic norms. Recent research from Groundwork Collaborative found that corporate profits drove over 50% of inflation during the second and third quarters of 2023.

Corporations have enjoyed these runaway profits despite rising costs, in part due to their successful use of pricing strategies. This paper overviews some of the most common pricing strategies with a focus on what is commonly known as “shrinkflation,” or the practice of decreasing the size or quantity of a product while keeping the price the same or higher. While shrinkflation is not new, it is arguably the most deceptive pricing practice companies use and has come under renewed scrutiny as Americans face grocery prices 25% higher than prior to the pandemic. We find that as much as 10% of inflation in key product categories can be attributed to shrinkflation. To better understand when companies look to shrinkflation instead of other pricing strategies, we also present excerpts from transcripts of earnings calls in which Fortune 500 CEOs talk to their investors about their shrinkflation practices. In these calls, companies report that shrinkflation accounts for as much as 20% of their net price hikes.

Download the full report here.

Types of Pricing Strategies

List price hikes

Corporations have employed several strategies for increasing their profit margins despite rising costs. First, they’ve executed aggressive increases in their list prices, passing along not only their rising costs, but also going for more. Companies have been quite candid with investors about this tactic, a topic Groundwork has covered at length, even going so far as to stress that “…we want to make sure that we’re not leaving any pricing on the table. We want to take as much as we can….”

“...we want to make sure that we’re not leaving any pricing on the table. We want to take as much as we can...”

Recently, as their own costs have declined or normalized, corporations have expanded their margins even further by maintaining high list prices instead of passing their savings along to customers. A recent paper from the Groundwork Collaborative illustrates this phenomenon with an example from the highly concentrated diaper industry, where giants Procter and Gamble (Pampers, Luvs) and Kimberly Clark (Huggies, Pull-Ups) control up to 70% of the market. Diaper prices have increased more than 30% since 2019 as prices for wood pulp, the main absorbent ingredient in diapers, soared.

But in 2023, the price of wood pulp declined by 25%. Despite this decline, Procter and Gamble and Kimberly Clark have used their pricing power to keep diaper prices high, and expand their profit margins considerably. Both companies recently told investors they expected wood pulp price declines to fuel major expansion in profit margins over time as they stuck to higher prices but saw their input costs fall.

The diaper industry is just one example of corporations exploiting their pricing power to expand margins as input costs normalize. The same is true for many consumer goods, including new and used cars, groceries, and housing.

Premiumization

In addition to executing aggressive list pricing, companies also use premiumization to increase net pricing, or the price of a product after taxes, fees, and discounts are considered. Premiumization is a strategy businesses use to get customers to pay higher prices than they normally would for a brand or product, by making their products seem better or more luxurious than the usual options, or by introducing a new item at a higher-price point to stretch the prices of lower-priced items in the category upward.

Colgate’s introduction of a $10 tube of toothpaste illustrates this strategy. In 2022, Colgate-Palmolive explained that the introduction of its new Optic White Pro Series toothpaste was vital to its ability to raise prices, driving profits. The strategy was straightforward: by introducing a $10 tube of toothpaste the company could also raise prices slightly on all lower-priced tubes along the pricing ladder, which would now be cheaper than the top-shelf tube, even at their new higher price points.

Price pack architecture or “shrinkflation”

A final pricing strategy is shrinkflation, or the practice of decreasing the size or quantity of a product while keeping the price the same or higher. Shrinkflation allows companies to pass on increased costs or to increase net pricing without overtly hiking their lists prices. Shrinkflation is an important pricing strategy in companies’ toolkits because consumers are less sensitive to changes in size than changes in price. Thus, when a company is worried they may not be able to increase list prices any further without fear of consumer blowback or a decline in sales, they may shift to shrinkflation.

Shrinkflation allows companies to pass on increased costs or increase net pricing without overtly hiking their list prices.

Shrinkflation is not always an easy strategy to deploy. Shrinking package sizes may require retooling and refitting assembly lines and manufacturing processes, reevaluating nutritional information and changing and reprinting nutrition labels, changing shipping practices, and more. Companies have to expect to see big revenue gains from shrinkflation to make it worthwhile, and it is typically the largest companies, those with vertically integrated supply chains, that are able to deploy this practice profitably and effectively. Small businesses that are more reliant on third-party vendors and suppliers are less likely to pursue shrinkflation.

There are two good sources of data on shrinkflation. The first is corporate earnings calls. While shrinkflation is not openly discussed on earnings calls, companies often reference “price pack architecture,” which is the strategy behind arranging products and their packaging sizes in order to influence consumer behavior and optimize sales. Reporting shows that companies often cite price pack architecture to introduce smaller packaging sizes or adjust product quantities within a package while keeping prices relatively stable.

When citing price pack architecture, companies may mean literally reducing the ounce weight of a certain good. But it can often mean introducing new smaller portions that can be sold at a higher weight per ounce. Companies may then use the new price of a smaller product to raise prices on larger products up the pricing ladder (a form of premiumization). New ‘premium’ products can be introduced that are also both pricier and smaller, which permit lesser price hikes on their other products. A related phenomenon called “skimpflation,” is the practice of skimping on the quality of an item including by substituting higher-priced ingredients for lower-cost ones.

Companies often mask these strategies as responding to ‘consumer preferences,’ even if that preference is simply for a cheaper option as other goods become more expensive. Some even frame these decisions as a matter of health, as the new smaller packages are described as ‘portion control’ for health-conscious consumers, or as a strategy to reduce emissions, as smaller products take up less space in a delivery truck.

A second source of data on shrinkflation comes from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). The BLS collects data on “shrinkflation,” or downsizing, as part of their effort to document inflation. The BLS’s primary measure of inflation is the consumer price index (CPI), which measures changes over time in prices paid by urban consumers for a market basket of goods and services. In order to accurately capture price changes, the CPI must also capture implicit price increases (decreases) when products are downsized (upsized). Think of it this way: if you are used to buying twelve cans of soda for $6 but the manufacturer reduces the number of cans in the package to ten but keeps the price at $6, then the price per can increases from $0.50 per can to $0.60 per can. These changes in the unit price of goods are fed into the CPI for a more accurate picture of inflation.

To understand how much of the inflation consumers are experiencing is being driven by these changes in the unit price of goods, the BLS constructs what they call a “research index,” which eliminates the price increases that result from downsizing. By comparing the research index and the CPI index, BLS economists can understand how much of the increase in prices is driven by shrinkflation.

In the sections below we summarize data on shrinkflation from both the BLS and earnings calls of Fortune 500 companies to show how shrinkflation is being used to expand corporate profit margins during this period of high inflation.

Data on Shrinkflation

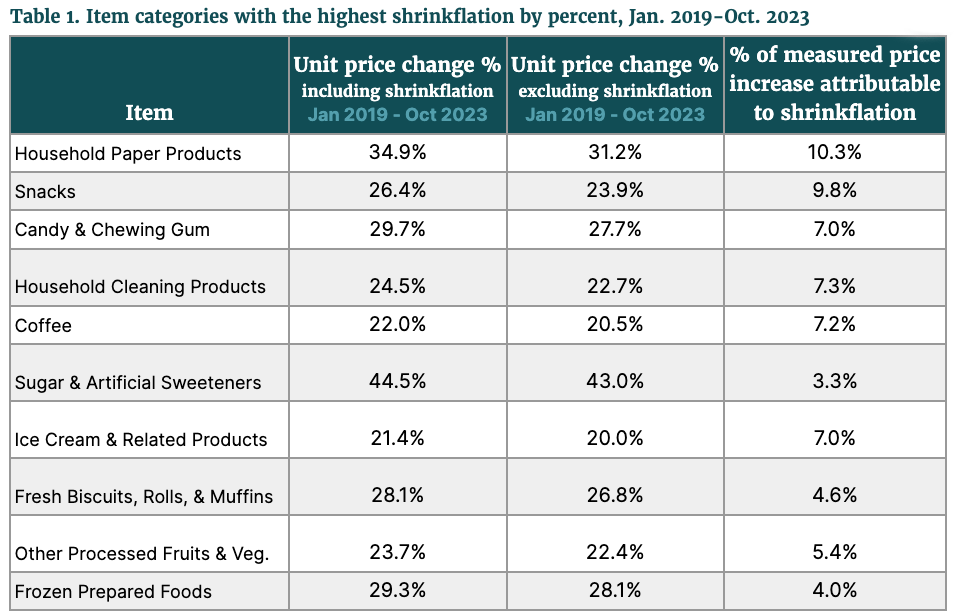

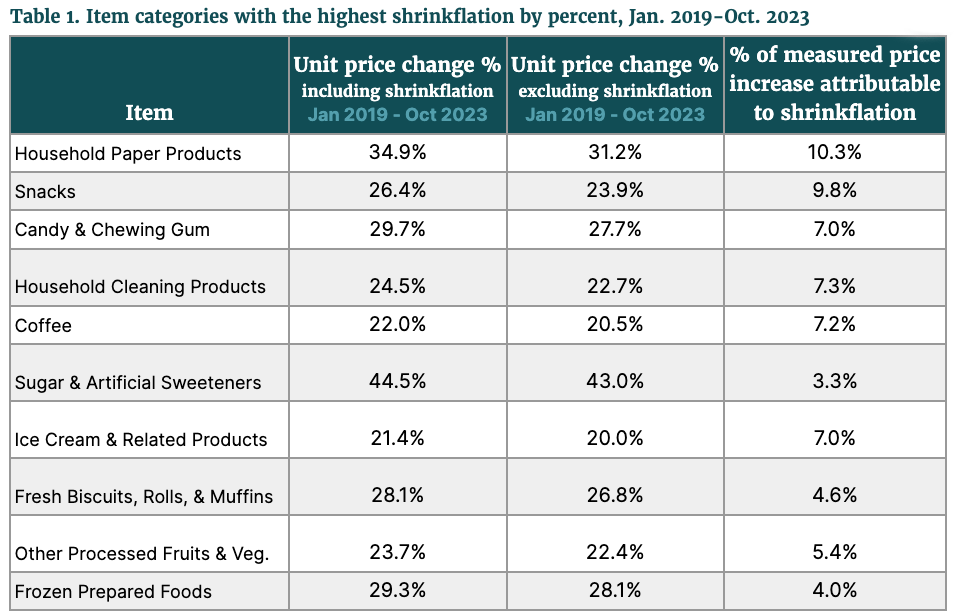

Table 1 lays out the product categories that have seen the most shrinkflation from January 2019 to October 2023. The second column shows the percentage change in prices accounting for the implicit price increase that results from shrinkflation. The third column reflects the “research index,” or the percentage change in prices without accounting for changes to the unit price of goods. The final column tells us what percent of the price increase is the result of shrinkflation. For some essential goods like household paper products (e.g. paper towels) and snacks, shrinkflation accounts for about 10% of the price increase consumers experienced during this time period.

Source: BLS Appendix Table A

Big Profits in Small Packages

Although inflation has come down considerably from its peak, prices remain elevated, and many Americans report significant levels of concern over high prices for essentials. Recent research from Groundwork Collaborative found that corporate profits drove over 50% of inflation during the second and third quarters of 2023.

View Full Report

Case Studies: CEOs Weigh in on Price Pack Architecture and Shrinkflation

In quarterly earnings calls with investors and analysts, corporate executives are candid about their future plans to downsize product quantities by playing with “price pack architecture,” as well as the profits they plan to derive from doing so. Below are several case studies from companies that practice shrinkflation.

Corporate executives are candid about their plans to downsize product quantities by playing with “price pack architecture” as well as the profits they plan to derive from doing so.

General Mills: “Reducing global emissions” with shrinkflation.

General Mills was reported to have cut the size of its ‘family size’ cereal boxes from 19.3 ounces to 18.1 ounces without any change in price. When asked about these reductions by NPR, General Mills claimed, “this change also allows more efficient truck loading leading to fewer trucks on the road and fewer gallons of fuel used, which is important in both reducing global emissions as well as offsetting increased costs associated with inflation.”

When speaking to investors, however, General Mills does not invoke gas prices or emissions. In a 2021 earnings call, their CEO told analysts “we will realize pricing. We’ll also, just we will use all of the tools, and that includes list pricing. But it’s list pricing. It is price pack architecture. It’s how we manage trade and then, finally, price and mix. We’ll need to use all those levers.”

Another executive on a 2022 earnings call touted, “it’s not just list pricing, it’s promotional optimization and mix and pack price architecture. And by leveraging all those tools, we believe that we’ll be able to combat inflation as we move forward as well.” That same executive emphasized at a 2021 investors conference that, “We have experts really in pricing, and they’ve been invaluable as we put together plans to really tackle the inflation coming our way. So we’ve worked hard to put — use the entire [Strategic Revenue Management] toolbox. So that’s everything from list prices to pack/price architecture, to mix, to promotional optimization. We’re leveraging all of those tools. We’ve put together strong stories. And with good rationale, we were able to get the pricing sold into the majority of our customers.”

Utz: Shrinkflation is “the path to higher margins,” accounting for roughly 20% of “net price hikes”

Snack company Utz reportedly cut the size of pretzel jars from 28 ounces to 26 ounces, while their potato chip bags shrank from 9.5 to 9 ounces. Utz’s CEO boasted on a 2022 earnings call that “our pricing is building significant benefit with ongoing momentum, not only from the pricing and price pack architecture initiatives from 2021, but also from our 2022 pricing actions.”

In 2021, Utz CEO told analysts that “the path to higher margins is also underpinned by our price pack architecture initiatives, which includes better trade management and higher net price realization.” When specifically asked how much price pack architecture contributed to their price increases, Utz CEO admitted it was roughly one-fifth of their net price hikes: “The weight out in terms of price pack architecture, that’s probably a rough number, maybe only about 20% of the total. Most of it is in either pricing or a combination of pricing plus sort of velocity and timing and depth and quantity of promotion. But it’s primarily in pricing and trade as opposed to weight outs or significant changes to the architecture of the units themselves.”

PepsiCo: “We just took a little bit out of the bag.”

PepsiCo has been caught reducing the size of products like their Fritos Scoops and Gatorade Bottles. When questioned by reporters about smaller Doritos bags, PepsiCo admitted, “we took just a little bit out of the bag so we can give you the same price, and you can keep enjoying your chips.” With investors, PepsiCo has been more open about its strategy to boost profits by shrinking quantities. In October 2022, their CEO explained that “we’re looking at multiple ways to increase our revenue per kilo in this case with continuing to maintain the consumer in our brands and obviously gain share as we do that. So that’s the strategy. We’ll use multiple levers. So visual pricing, lower promotions, pushing for the formats where we have higher revenue per liter or per kilo, moving into channels, obviously, where we can price more because the consumer has different price expectations….And that’s the way Frito’s doing it, but the same is being done in beverages North America.”

One year later, in October 2023, PepsiCo’s CEO was even more blunt with an analyst: “you mentioned consumers moving to smaller packs. We’re also, in a way, facilitating that through our pricing and mix strategy.” Another hint of their strategy can be found in their revenue data, where for the year ending in 2023, the company reported a 13% benefit to net revenue year-over-year percentage change due to “effective net pricing.” According to PepsiCo, “effective net pricing” is defined as “the year-over-year impact of discrete pricing actions, sales incentive activities and mix resulting from selling varying products in different package sizes and in different countries.”

PepsiCo’s tactics have caught more than the eyes of consumers. Starting in September 2023, the French supermarket chain Carrefour began planning “shrinkflation” warnings on products like Lipton’s Iced Tea. In January 2024, Carrefour went as far as to declare it would no longer stock PepsiCo products at all due to unacceptable price increases.

Hershey’s: “Changing the game” with shrinkflation.

Hershey’s has also taken to shrinking the sizes of its products to increase their profits. The Washington Post reported that “a bag of dark chocolate Hershey’s Kisses is now a couple of ounces smaller than before. A two-pack of Reese’s Peanut Butter Cups is a tenth of an ounce lighter.” Hershey executives have repeatedly stressed the importance of price pack architecture strategies in driving their profits, telling analysts in 2024 that they “are actively evaluating price pack architecture opportunities to help ensure we have the right offerings, and price points to meet consumers’ changing needs.”

In February 2022, Hershey’s CEO boasted the company “started to invest in price pack architecture and look at, how can we generate price realization without a list price but by changing the game.” At the company’s investment day in March 2023, Hershey’s CEO described “price pack architecture as a key lever in our pricing strategies.” In April 2023, Hershey’s CFO noted that “confection margins have been strong, but even in the future, across all levers, pricing, including price pack, architecture and mix, and other things, we want to continue to put upward pressure on our margins because that’s part of our growth formulas so.”

Procter & Gamble: “We had to make a tough choice.”

Procter & Gamble has been connected to repeated instances of shrinkflation. The Associated Press reported the company downsized its Pantene conditioner without reducing the cost, Quartz confirmed the reduction of Crest toothpaste and Bounty paper towels, and a consumer advocate found the company cutting the size of its Gain detergent and Charmin toilet paper packs without a price decrease. When ABC15 Arizona found Procter & Gamble cutting the size of 7-ounce dish soap to 6.5 fluid ounces, the company defended the change as a result of improved quality: “We recently made improvements to Dawn Ultra & Dawn Ultra Platinum to fight grease better than ever. In order to do this, we had to make a tough choice. Rather than increasing the cost of our products, we have changed some of the bottle sizes.”

In May 2022, Procter & Gamble’s CFO obliquely noted these changes when asked why the company had not raised prices even faster. He explained, “The second component is some of our categories are very price elastic, and they serve consumers across multiple income levels. And for some of those consumers, value per unit is very important. For some of those consumers, cash outlay is very important. So where we had to make adjustments to protect key price points, especially for channels where those more constrained consumers shop, it takes time. We need to adjust the pack count. We need to adjust the artwork on the pack count. We need to align retailers because it has implications on the shelf, on the shelf setup.”

Kimberly-Clark: “If the price goes up on bath tissue, [it] generally doesn’t mean you’re going to use the bathroom less, right?”

Kimberly-Clark, the personal care company that manufactures products like Cottonelle, Scott, Kleenex, Huggies, and Kotex, is another repeat shrinkflation offender. The company has been caught shrinking the rolls in its Cottonelle toilet paper packs and the number of tissues in its Kleenex boxes. One investigator even found that its Scott toilet paper rolls, while maintaining the same number of sheets, are thinner and rougher with 20% less paper fiber.

While the company typically refuses to comment on media inquiries, its CEO has been refreshingly open when talking with investors. On an April 2023 earnings call, Hsu explained why he believed his company could get away with these kinds of price hikes: “If the price goes up on bath tissue, generally doesn’t mean you’re going to use the bathroom less, right? And so, I think we do operate in essential categories that have less elasticity.” In July 2023, Mike Hsu told analysts that “we’re doing things like adjusting counts to make sure our large packs remain competitive and affordable. We’re sharpening our entry price points and small format stores to make sure that consumers can afford to be in the category.”

“If the price goes up on bath tissue, generally doesn't mean you're going to use the bathroom less, right?”

At an investor conference in September 2022, Hsu stressed, “we believe we have to get our margins to an expansion mode. We weren’t planning on taking $3 billion of inflation. So we’ll recognize that, that’s something we have to manage through, but we’re committed to that. I was here for that — for the — maybe the expansive part of the recovery from 2008. And so — and I think the tactics are similar, which is what we applied was very good programs around revenue management, including pricing, but also pack count and sheet count and things like that.”

Mondelez: Shrinkflation as “portion control”

Snack manufacturer Mondelez has confirmed they reduced the weight of their Wheat Thins Family Size Original from 16 ounces to 14 ounces. In the UK, the company admitted they had shrunk the Cadbury Dairy Milk sharing bar by 10% without any change in price. Cadbury Dairy Milk Giant Buttons large sharing bags were cut by 23%. In the US, Mondelez decreased family-sized packs of Double Stuff Oreos by 6%. In Korea, Mondelez reportedly cut the weight of Halls cough drops by nearly 20%.

Mondelez’s CFO previewed some of these changes at a consumer analyst conference in 2021, saying, “we also plan to better utilize revenue growth management in terms of mix, price pack architecture, promotions and smart pricing to grow both top and bottom lines.” In what could be a healthier twist on shrinkflation, Mondelez’s CEO boasted in 2023 that “We are offering a broader range of portion-controlled packs and products, but also our portion-controlled education campaigns both digitally and on pack.”

Conclusion

When companies have pushed prices to the maximum consumers will pay, they start shrinking quantities and holding prices constant. Shrinkflation is a particularly deceptive pricing strategy and companies know this. In fact, research shows that consumers are more sensitive to price changes than size changes. During this period of high inflation, where rising prices are putting a squeeze on household budgets, shrinkflation just adds insult to injury. Meanwhile, corporations have enjoyed profit margins well above historical norms.

During this period of high inflation, where rising prices are putting a squeeze on household budgets, shrinkflation just adds insult to injury.

Consumers should not be on the hook for uncovering shrinkflation. That’s the job of policymakers. President Biden has been outspoken in calling out corporations who are raising prices beyond what their costs justify or deploying descriptive shrinkflation strategies, telling businesses in November, “It’s time to stop the price gouging,” and airing a Super Bowl video condemning shrinkflation. President Biden has also cracked down on the use of junk fees throughout the economy, from credit card late fees to hidden fees tacked on to used car sales by auto dealers, to resort fees at hotels. These junk fees increase the total price consumers pay for goods beyond the advertised list price and often come as a surprise to consumers. Deceptive pricing practices like junk fees and shrinkflation are exploitative and should be curtailed. President Biden’s efforts in this space will go a long way to restoring a level playing field for consumers.

United States Senator Bob Casey from Pennsylvania has introduced legislation to prohibit shrinkflation. His Shrinkflation Prevention Act would direct the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to regulate shrinkflation as an unfair or deceptive act or practice, which would prohibit manufacturers from engaging in shrinkflation. It will also authorize the FTC and state attorneys general to pursue civil actions against corporations engaging in shrinkflation.

In addition to new legislation, the FTC could explore the extent to which their labeling authority under the Fair Packaging and Labeling Act or their enforcement authority to prevent unfair and deceptive practices under section 5a of the FTC Act could help to curb some types of shrinkflation. Grocers abroad have recently gained national attention for their prominent placement of shrinkflation labels on products and this could be an effective strategy at home as well.

Finally, policymakers should also consider using the tax code to disincentivize profiteering by companies engaging in aggressive pricing strategies, including shrinkflation. Companies will have less incentive to overcharge customers if they have to ship a greater share of the spoils to the Treasury Department. A recent report from the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy found that some of the largest companies practicing shrinkflation were consistently profitable from 2018 through 2022 and paid incredibly low effective tax rates during this period, thanks to changes in the corporate rate under President Trump in 2017. Congress should look at increases in the corporate tax as part of its inflation-fighting toolkit.

In an era where inflationary pressures loom large over the economy, businesses have increasingly turned to innovative pricing strategies to preserve or enhance profit margins without overtly alarming consumers. Shrinkflation has emerged as a particularly cunning strategy. By examining evidence from earnings calls, industry practices, and official government statistics, this analysis highlights the unique and substantial contribution of shrinkflation to inflation and the need for greater transparency and accountability in corporate pricing practices.